Have you lost sleep at any time in the past year? You are not alone. Uncertainty about the future, constant media coverage of the pandemic, rapid changes in our lifestyles and work patterns, and financial stress are all factors that have contributed to poor sleep health. In contrast, for others, time spent at home, the cancellation of social activities and curfew have improved their sleep.

Sleep health encompasses elements such as sleep quality, duration, regularity, and timing. An important lesson from this collective disruption is that sleep health is not only the result of our individual choices. It is also linked to our life context. It is crucial to look at the factors in our environment and communities that influence our health and well-being.

Health beyond individual choices

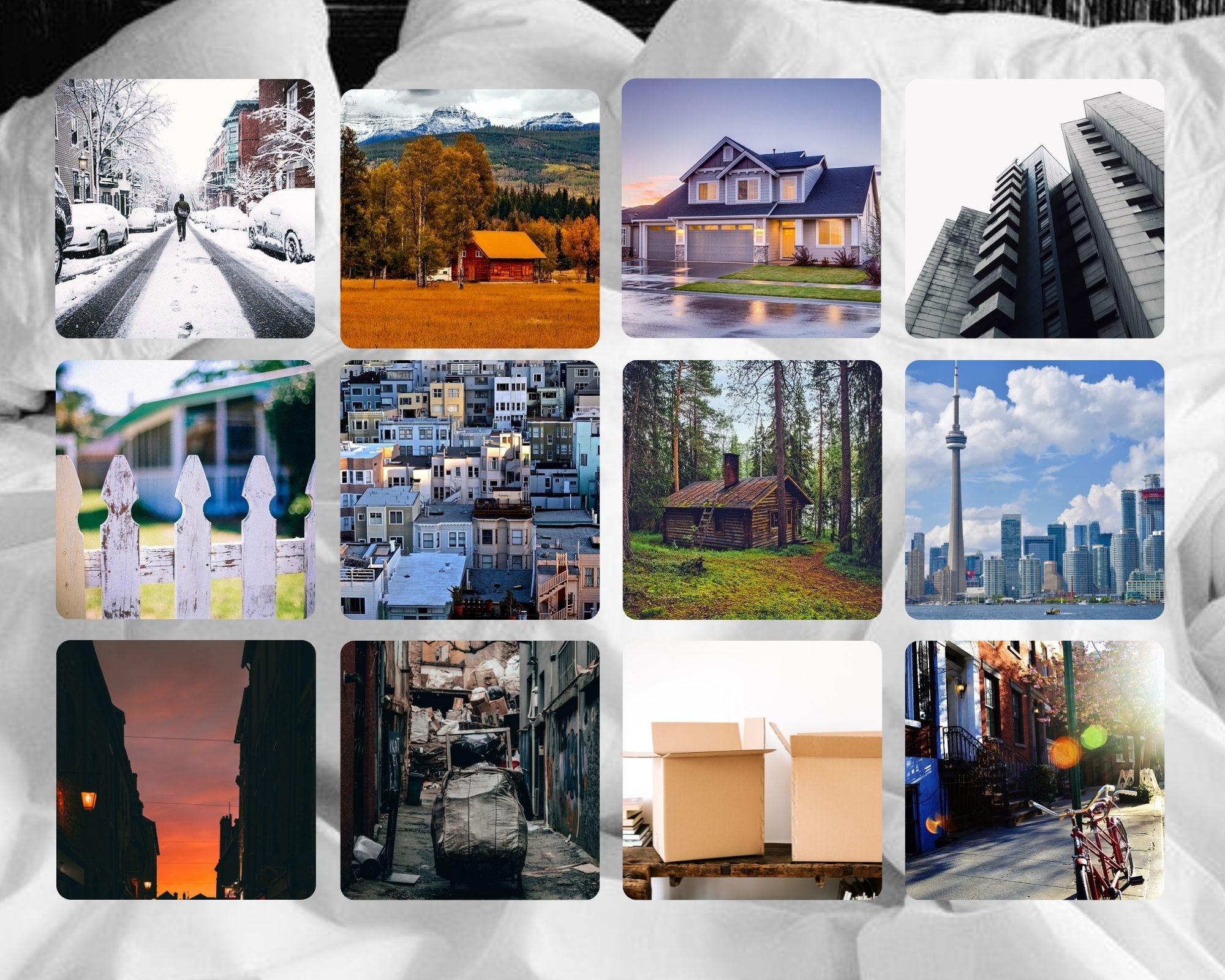

These factors, which are called social and environmental determinants of health, can explain why, for example, in 2012, the healthy life expectancy of the most advantaged men was 9.7 years higher than that of the most disadvantaged men in Quebec. For women, a similar disparity of 7.5 years was observed. These differences between the most and least affluent groups reflects significant inequalities in the distribution of the resources that enable us to maintain a good health over time. But what are these factors? Income and education play an important role, of course, but so does the quality of our housing and neighbourhoods, whether it is noisy housing, access to infrastructures such as bicycle paths or green spaces, or the presence of healthy and affordable food sources. Living close to sources of pollution, or lack of neighbourhood social cohesion, including systemic discrimination, also contribute to explaining health inequalities. The COHESION pan-Canadian study was set up in 2020 to monitor the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on multiple social and environmental determinants and their consequences on mental health and well-being. One of many efforts includes exploring the link between satisfaction with housing conditions and sleep duration.

The housing conditions in which we live and one’s access to home ownership depend largely on income, personal wealth and the local housing market. The less privileged are more likely to live in substandard conditions and spend a significant large portion of their income on housing, sometimes affecting their ability to meet other basic needs such as food, medicine, or heating in winter. Numerous studies have found that problems of substandard housing are related to household income and the cost of rent in the private market. The health impacts of poor housing are well documented: respiratory diseases, stress, mental health problems, nutritional deficiencies, and many more. The World Health Organization has even declared that “access to quality housing is a prerequisite for a healthy life”.

What about sleep?

To understand how housing status is related to sleep health during the COVID-19 pandemic, the COHESION study explored whether one’s status as renter or owner, and satisfaction with housing conditions were associated with sleep duration. Based on the scientific literature showing a social gradient to sleep health, the researchers hypothesized that renters would have a higher likelihood of being short sleepers. To answer this question, the COHESION team analyzed the profile of 339 adults (average age 54 years, 78% women), some of whom reported not meeting the recommended amount of sleep of seven hours per night.

Results show that renters are two times more likely to sleep less than seven hours per night, compared to homeowners.

To try to explain this difference, the team considered different factors: age of the respondent, income, satisfaction with the available space at home, satisfaction with the number of bedrooms and satisfaction with the condition of the dwelling (i.e., How satisfied are you with the condition of your dwelling?). In these analyses, only dissatisfaction with the housing conditions (excluding the size of the dwelling and the number of bedrooms) increased the risk of sleeping less than 7 hours per night. In other words, it is not so much the fact of owning or renting that influences sleep duration, but rather the fact of being dissatisfied with one’s housing conditions. The sources of dissatisfaction can be diverse: noise, poor thermal insulation, poor maintenance, being too expensive, or located in a neighbourhood with poor infrastructure and services.

According to the Census, nearly two million households in Canada are in core housing need, meaning that their housing is considered inadequate, unaffordable, or unsuitable in size. These research findings are set against the backdrop of a housing crisis across the country, particularly in the major metropolitan areas. Rising property prices and construction costs, as well as a shortage of affordable housing, are forcing low-income households to occupy substandard housing if they cannot find better accommodation. The results of the COHESION study suggest that these households are more likely to have poorer sleep health.

So, what can we learn from this? Addressing housing conditions could be an important lever to improve sleep duration and contribute to our collective health and well-being.